How the Oligarchs Hypnotized Labor Leaders to Betray Working Class Communities of Color.

Opened in 1889, O’Connor Hospital was the first in the city of San Jose, and the second in California to be chartered and managed by the Daughters of Charity, a 400-year-old Catholic mission founded by St. Vincent de Paul. Its benefactor, Judge Myles P. O’Connor, made his fortune in mining and he and his wife, Amanda, were two of Silicon Valley’s first philanthropists. They had originally planned to open an old-age home and an orphanage, but the local Archbishop convinced the couple that the needs of what would grow to become the state’s third most populous city were far too prolific to address only that which vexed the very young, and the very old.

For the next 125 years, the Daughters of Charity faithfully served San Jose’s sick, pregnant, and poor, the hospital’s fortunes rising and falling in tandem with that of Santa Clara County’s laboring classes. With paychecks buoyed by postwar productivity and assertive trade unions, the order built a new, state-of-the art campus on the city’s east side in 1953, just as Americans were bursting at the seams with hope, and babies.

Similar to the protagonist in Ernest Hemingway’s novel, The Sun Also Rises, however, O’Connor went broke, gradually at first, and then suddenly, as good-paying jobs dried up, culminating in the ruinous 2008 recession that left millions of Californians unable to pay their hospital tab. Forced to borrow heavily just to stay afloat, the Daughters of Charity Health System announced in 2014 what would’ve once been unthinkable: a sale of its network of six hospitals.

More jarring still was the colorful streetscape that greeted morning commuters on Forest Avenue as they approached O’Connor’s main gate in the first days of 2015. As the low-watt January sun doused the Santa Cruz mountains in a champagne-colored dew, motorists were visibly puzzled, some even scratching their heads as they passed by.

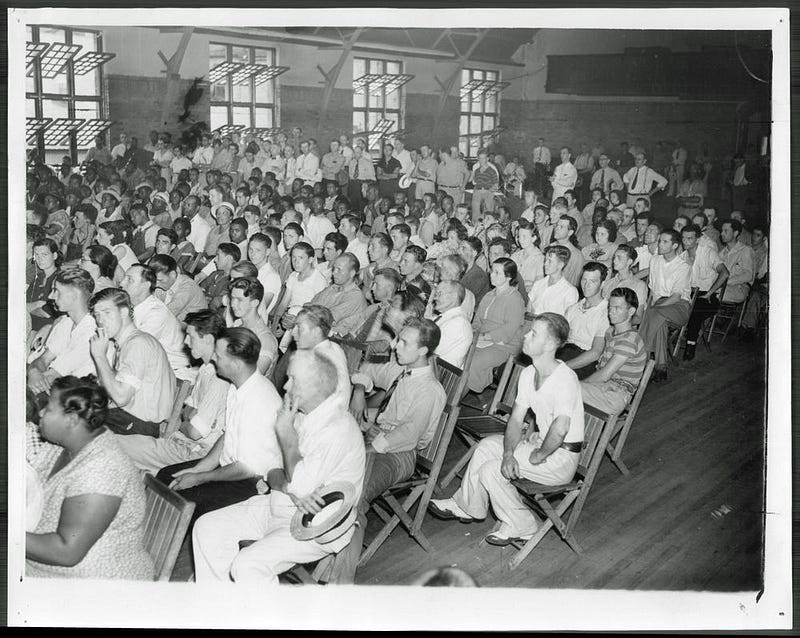

On the campus’ north lawn, nearly 100 protesters clad in robin’s-breast red, chanted, cheered and hoisted placards that read: “Nurses and nuns agree: Approve the Sale.”

To the south, maybe 20 yards away, stood another 100 or so demonstrators clad entirely in blue, brandishing signs that read: “Save our Hospital; Reject the Sale.”

The dueling rallies prefaced a public hearing by California’s State Attorney General Kamala Harris, who is legally required to approve the sale of nonprofit hospitals, and pitted one powerful labor union — the California Nurses Association in red — against another — the Service Employees’ International Union, in blue.

Dubbed by the Nation Magazine as the country’s most progressive trade union, the CNA and its umbrella organization, National Nurses United, endorsed a proposal by Daughters of Charity executives to sell the chain to Prime, a southern California-based healthcare provider with a reputation for ripping off Medicaid, its patients, and its workforce. A 2014 federal audit of Prime hospitals, for instance, found 217 cases of improperly diagnosed kwashiorkor, a form of malnutrition that is seldom seen in the US, and typically found only in the global South. Unsurprisingly, Medicaid reimbursement rate for the the disease is quite high when compared with other maladies.

The SEIU, on the other hand, favored a sale to a Wall Street hedge fund named Blue Wolf with no management experience in the healthcare industry, but a demonstrated proficiency for dismantling businesses and auctioning its parts off to the highest bidders.

But here’s the thing: San Jose’s working-class communities — a Benetton-blend of Latinos, south Asians, Blacks and Whites — wanted neither, Prime least of all.

Had they bothered to show up for any of the dozen or so community stakeholder meetings held in 2014, the CNA’s leadership might have known this. But Bob Brownstein, the executive director of the civic organization, Working Partners USA, could only remember seeing a CNA labor representative at a single meeting, and if he chimed in on the discussion, Brownstein couldn’t recall.

Labor representatives for the SEIU, on the other hand, and Blue Wolf executives were fixtures at the stakeholders’ meetings.

“I don’t think either union did much of anything,” Brownstein recalled more than a year later, “but SEIU was clearly more comfortable in dealing with the community. As I recall, there was someone from Blue Wolf and the SEIU at every meeting and they answered every question that everyone put to them. They were clearly trying to generate answers and they even made some changes to the original proposal” to win the community’s approval.

“Their offer was more opaque but they did a much better job than Prime did in acknowledging community concerns. We never trusted Blue Mountain but the community was much more worried about Prime.”

So much so that a coalition of 15 civic groups wrote a joint letter to Harris urging her to veto the sale to Prime. The stakeholders’ clear preference was Santa Clara County which had bid on O’Connor, and whose health care network had a regional reputation for providing quality care to the uninsured that was second only to O’Connor’s.

But Daughters of Charity executives did not want to break up the set, so-to-speak, and preferred selling all six hospitals to a single bidder.

“I don’t know why the California Nurses Association didn’t help us push the county’s bid,” said Grace-Sonia E. Melanio, Communications Director for Community Health Partnership, which was one of the authors of the letter to the attorney general’s office.

“I assume it was because they don’t represent county nurses but I don’t know that for a fact.”

By January of 2015, Brownstein, Melanio and others knew that shifting the conversation from the two labor-backed bidders to the county’s bid was a longshot, at best.

Still, Melanio recalls her astonishment at seeing the the tsunami of red and blue as she pulled into the O’Connor parking lot ahead of that January public hearing.

“I was shocked,” she said, “to see that the unions had the community outnumbered by roughly 100 to 1.”

“You Got to Dance with Them That Brung You”

The question of who killed organized labor in the US has always been something of a whodunit for me, until I went to work as a communications specialist for the California Nurses Association in January of 2015.

The action at O’Connor was my first week on the job and the hospital’s ultimate sale to a Wall Street hedge fund was tantamount to an exhumation. After examining the cadaver close up, I can report that all evidence identifies the killer beyond a shadow of a doubt:

It was a suicide.

What proved the undoing of the labor movement was not the bloodlessness of conservatives, but the faithlessness of liberals; not the 1 percent’s dearth of compassion, but the 99 percent’s failure of imagination; not the corruption of the managerial class but trade union leaders’ desertion of the very communities that made the American labor movement a force to be reckoned with in the first place.

“You got to dance,” the immortal Molly Ivins once wrote, “ with them what brung you.” After collaborating with workers of all races to create a middle-class that stands as the singular achievement of the Industrial era, unions switched dance partners mid-song.

In championing Prime Health Care, the nurses’ union, and its Executive Director, RoseAnn DeMoro, carried water for a venal corporate class in much the same fashion that the Democratic Party, and its titular leader, Hillary Clinton, runs interference for Wall Street, leaving the people of San Jose to choose from the lesser of two evils, just as voters in next week’s presidential ballot have no good options.

This is no coincidence. Beginning in earnest with Wall Street’s 1975 takeover of New York City’s budget, corporate executives have wooed both Democrats and labor union leaders with increasing assertiveness, in a concerted effort to thwart the interracial labor movement that is the only fighting force to ever battle the plutocrats’ to a draw.

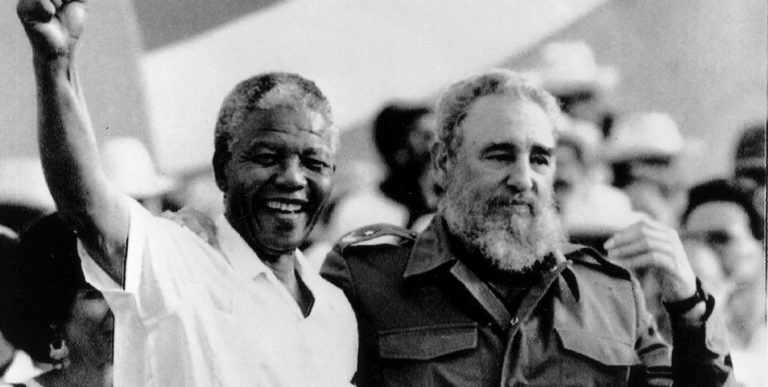

To put only slightly too fine a point on it, financiers’ courtship of labor in the postwar era mirrors Napoleon’s recruitment of Haiti’s mulattoes to help put down the island’s slave mutiny. Both counter- revolutions drove a wedge through the opposition with a psych-ops campaign that can be reduced to a question of identity:

Are you a worker, or are you white?

No More Beautiful Sight

The Bay Area can make a credible claim to being the birthplace of the modern labor movement. When West Coast longshoremen went on strike at the height of the Great Depression, Blacks who had consistently been rebuffed in their efforts to integrate the docks, jumped at the chance to work, albeit for smaller paychecks than their white peers.

Confronted with a failing strike, the head of the longshoremen’s union, an Australian émigré named Harry Bridges, toured African American churches on both sides of the Bay bridge, according to the late journalist Thomas Fleming.

From the pulpit, Bridges acknowledged the union’s historical mistreatment of Blacks, but promised skeptical parishioners that if they respected the pickets, they would work the ports up and down the West Coast, earning the same wage as white dockworkers.

They did, and the strike’s subsequent success triggered a wave of labor militancy that not only imbued the economy with buying power, but connected workers’ discontent with broader political struggles for affordable housing, free public education, infrastructure improvements, and civil rights.

“Negro-white unity has proved to be the most effective weapon against the shipowners,” the historian Philip S. Foner quoted a dockworker saying in his book, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, “against the raiders and all our enemies.”

When Oakland’s two chic department stores, Kahns and Hastings, denied pay raises to their mostly women employees in 1946, nearly 100,000 union members — mostly men — walked off the job in solidarity.

But they didn’t stop there, shutting down the whole of Alameda County for the better part of two days, ordering businesses to close, and turning back deliveries of everything other than essential medical supplies and beer, which they commandeered to hold a bi-racial bacchanal in the streets of Oakland, dancing, singing, and exulting in the power of the many.

It was the last general strike in US history; within months, Congress overrode President Truman’s veto of the Taft-Hartley Act which, among other things, outlawed so-called sympathy strikes, and mandated trade unions to expel Communists from their ranks.

Still, the working class maintained its swagger for another generation.

Invoking eminent domain, the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency razed thousands of structures in the city’s “blighted” Fillmore neighborhood, forcing nearly 10,000, mostly Black households to relocate, and transforming Geary Street into an eight-lane monstrosity which sealed off the Fillmore from the whiter and wealthier Pacific Heights.

In a 1963 interview with the Boston television station WGBH, about his iconic documentary, Take This Hammer, James Baldwin said this:

“A boy last week — he was 16, in San Francisco — told me on television….He said, “I’ve got no country. I’ve got no flag.” Now, he’s only 16 years old, and I couldn’t say, “You do.” I don’t have any evidence to prove that he does. They were tearing down his house because San Francisco is engaging — as most Northern cities now are engaged — in something called urban renewal, which means moving the Negroes out.”

Among those who took notice of the Fillmore’s gentrification was Lou Goldblatt, who was, at the time, the second-in-command of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, the very same union that had integrated the West Coast’s docks.

“There was no reason why the pension funds should just be laying around being invested in high-grade securities, Goldblatt later recalled. I thought there was no reason why that money shouldn’t be used to build some low-cost housing.”

The ILWU created the Longshore Redevelopment Corporation to pounce on the three city blocks–out of a total of 60– that the city had set aside for affordable housing.

In her 1964 letter to the San Francisco Chronicle, Josephine Solomon described her new digs: “I’ve just moved into my new home in St. Francis Square…and living here is quite clearly going to be exhilarating and, more important, the best possible place in which I can raise my children. About 100 families have already moved in…and we have representatives of all races and colors living together as neighbors. There is no more beautiful sight in this town than our marvelous, mixed-up collection of white, brown, and yellow children playing together in the sunny community square every afternoon.”

Who’s The Boss?

“C’mon people, what are some more nurses values?”

I was nearly four months into my stint at the CNA when I found myself in a half-lit, mildewed, second-floor conference room in the union’s downtown Oakland office, seated among a clutch of maybe 7 or 8 other communications staffers, all but two of us–an Asian woman and myself–who are non-white.

The task this late April afternoon was to identify “nurses values,” which I had assumed meant that I would help pore over the results of a nurses’ questionnaire to produce a coherent ad campaign.

Instead, the communications manager, Sarah Cecile, stood astride an easel that leaned like a sprinter at the finish line, her magic marker poised to add to the wan list of nouns that glared accusingly at me, reducing Hegelian dialectical inquiry to a game of fucking charades.

“Wait,” I said, “we’re telling the nurses what their values should be? Shouldn’t we be asking the nurses what their values are, you know, like in a survey, or a poll?”

“That’s a bad word for us,” said a graphic artist who’d worked for the CNA for several years. “Polling is frowned upon here.”

“Maybe they know something I don’t,” I said sarcastically, “but if we’re telling the rank and file what to do, doesn’t that make the union just another boss that the nurses have to answer to?

Should communications organize a coup of sorts?” I asked provocatively.

When I returned to my office 30 minutes later, I had an email from De Moro’s secretary, summoning me to a meeting with the executive director the following morning.

This was extraordinary for a couple of reasons, not the least of which was that despite sharing the same floor as the executive staff, it was an unwritten rule that communications was to have no contact with top management. This directive went so far as to prohibit communications from either emailing executives directly, or from entering or exiting through the executives’ north wing.

Moreover, I was told that both the executive staff, and the board, were almost all lily-white, save for one Latino and one African-American on each.

What I remember most about the next day’s meeting is the mirthless half-smile that DeMoro wore like a mask for nearly the entire 45-minutes, reminding me of Sir Richard Burton’s description of Lucille Ball as “a monster of staggering charmlessness.”

She began by asking me if I had any ideas for trying to improve the union’s communications effort, which was odd, since she’d blown off an email with my suggestions for doing exactly that only weeks earlier.

“Anything we could do to make this more of a bottom-up effort would be to the union’s benefit,” I recall saying. “It seems we spend an awful lot of time trying to talk to people who really aren’t interested in what we have to say, and not enough rallying and organizing the community to put pressure on decision makers.”

By this time, California’s Secretary-of-State, Harris had already, effectively vetoed the sale to Prime by attaching such stringent conditions to the transaction that she knew no corporation would accept the terms. I had publicly predicted as much months earlier; knowing that Harris would rely heavily on Wall Street to finance her US Senate campaign, I’d proposed, unsuccessfully, writing articles interrogating the investment firm’s mishandling of other businesses it had acquired.

But DeMoro’s communications’ director, a walking mediocrity named Chuck Idelson, had all of the imagination of a lamp post, and only half the personality. His idea of media relations was sending out at least one anemic press release per day, then marshaling the entire communication staff for two days to badger journalists we had no relationship with to cover news conferences that were wholly absent any news. A North Carolina rally for the Robin Hood tax on Wall Street transactions was attended by two people, the parents of Cecile, the communications manager.

As presidential hopefuls began campaigning in Iowa ahead of that state’s all important caucus, the nurses’ union planned to launch an ad campaign against Wisconsin’s Republican Governor Scott Walker.

“Why in the world would you do that?” I asked Idelson one day in early 2015 just as the primary season was beginning to take shape.

“Well, Walker is really bad on labor,” Idelson said.

“All the Republicans are bad on labor,” I said. “All the Democrats too. You’re gonna tell the rank-and-file that you spent a quarter-of-a-million dollars to help send union-busting Hillary Clinton to the White House? Why don’t they spend that money on organizing, or on an ad campaign to support Black Lives Matter. Police violence against people of color is a public health crisis,” I said. “Who is more credible on that issue than nurses?”

Moreover, I said, a California-based trade union buying ads in Iowa with union dues will surely be used as a cudgel with which to beat organized labor upside the head.

I repeated my concerns to DeMoro, but with that awkward smile on her face, she made it clear that she shared neither my faith in the rank-and-file, or the community.

“The nurses have some issues,” she said at our meeting. “We need for more of them to support the Democrats and to work the phone banks and things like that,” she said. “And frankly,” she said, abandoning all pretense now, her smile dissolving into a contemptuous frown, “they need to be more progressive, more radical and to take more chances.”

DeMoro’s annual salary at the time was $359,000, more than triple the average nurse’s yearly pay.

U Ain’t White

Portraying Leftists as subversives, the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act required trade unions to weed out suspected communists, according to the historian Foner, by asking Black workers questions like:

“Have you ever had dinner with a mixed group?”

And this: Have you ever danced with a white girl?”

Whites were asked if they had ever entertained Blacks in their homes, and witnesses, Foner wrote, were asked “Have you ever had any conversations that would lead you to believe (the accused) is rather advanced in his thinking on racial matters?”

Dorothy Height, president of the National Council of Negro Women, would later acknowledge that this purge of communists from trade unions was akin to severing the umbilical cord while the baby was still in the womb, starving the most democratizing social movements of a vital fuel-source.

Much of the labor movement’s bandwidth however, could not be measured in muscle, or union-dues, but in imagination, as demonstrated by the ILWU’s Goldblatt’s vision of a Beloved Community, fashioned from the stevedores’ pension fund.

“So let’s all be careful,” United Auto Workers President Walter Reuther once said, “that we don’t play the bosses game by falling for the Red Scare.”

And then Reuther went on to play the bosses game, expertly, chasing Marxists from the union, isolating Black workers, and reverting to the anodyne reforms that characterized the ineffective, segregated unions before the 1934 San Francisco General Strike. So disillusioned were Black autoworkers with Reuther’s tripartite alliance with Detroit’s industrialists and the Democrats that by the late 1960s, many had begun to joke that the acronym UAW stood for “U Ain’t White.”

The tipping point, however, occurred in the midst of the 1975 fiscal crisis, when New York bankers hatched a scheme to recoup their losses on bad real estate investments from the wages, pensions, and subsidies shelled out to city employees and the working class. The facts were not on their side, and so the financiers played the only hand they knew to play: race.

Doubling down on the Birth-of-a-Nation narrative, the city’s oligarchs, and their friends in the media, portrayed Blacks as a menace to the civic project, exploiting racial resentment of a Black polity that had found its voice mostly through labor unions.

In a 1976 episode of the NBC television series, McCloud, titled “The Day New York Turned Blue,” the stetson-wearing New Mexico sheriff– an avatar for white, male supremacy– almost single-handedly rescues Gotham from ruin, largely by convincing an Italian cop named Rizzo to cross a picket line, and help repel an attack by the mafia, who ambush police headquarters to kill a mob attorney-turned state’s witness.

Aside from the mafia, the villains in this urban morality tale are the police union–led by the Bad Nigger that 1970s America loved to hate, Carl Weathers–which refuses to call off a labor walkout in the city’s time-of-need, and a prostitute who is drugging her clients–one an accountant visiting New York to audit federal bailout money–with a fatal, suffocating blue paint.

Playing the role of Rizzo in real-life was the head of the city’s largest municipal union, Victor Gotbaum. In his book, Working Class New York, the historian Joshua B. Freeman wrote of Gotbaum and his partner, Joe Bigel:

“Having seen the power of the financial community,the hostility of the federal government, and the divisions within the union movement, they shied away from a militant, independent labor strategy which might have led to them being blamed for a city bankruptcy. Instead, they preferred to make concessions and invest their members’ pension money in city debt in return for a place at or near the table, where discussions about the city’s future were being made by financiers, businessmen, and state and federal officials. Gotbaum became so entranced by the power elite . . .that within a few years he and (investment banker Felix) Rohatyin were calling each other best friends, even holding a joint birthday party in Southampton.”

DeMoro is an heir to Gotbaum, not Goldblatt. If she or any of her lieutenants had an ounce of imagination I never saw it. Consider that at no time during the Daughter’s of Charity sale, did I ever once hear anyone mention the possibility of pushing for legislation to convert O’Connor to a worker, or community-managed health co-op, similar to the ILWU’s response to the Fillmore’s housing crisis.

Shortly after Harris nixed the Prime deal, DeMoro called an emergency all-staff meeting in March of 2015, in which she bluntly asked the 65 or so staff members for their suggestions.

“If we don’t do something different now, we’re going to die,” she said.

A young Latina labor organizer raised her hand, and said: “Why don’t we start to build partnerships with the immigrant rights community that’s politically active and organizing across California,” I recall her saying. “We could really strengthen our own organizing capacity and deepen our roots in a community that is looking to join forces with institutional allies.”

You could’ve heard a gnat piss on cotton in Georgia.

Later, the young organizer would tell me privately me that had she been a white, male labor organizer, and replaced immigrant rights community with some off-brand faction of Silicon Valley white liberals, say Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, DeMoro would’ve been over the moon.

“Everybody knows that RoseAnn loves her white boys,” she said.

As for me, I was fired a week after proposing a coup because “you don’t seem happy here.”

It was May 1, or May Day.