In late March of 2019, the liberal British daily newspaper, the Guardian, published an op/ed by one of its columnists, Bhaskar Sunkara, the founder of Jacobin magazine. In the article, entitled To fight racism, we need to think beyond reparations, Sunkara, a socialist, concedes that there is indeed a strong moral case to be made for a just recompense for the descendants of American slaves but such a race-specific measure is impractical and even counterproductive for the embattled working class as a whole.

Referencing the black writer Ta-Nehisi Coates who is a prominent proponent of reparations, Sunkara wrote:

“But what kind of bureaucratic process would be necessary to identify who gets to receive the reparations Coates supports? It can’t simply be race, because recent immigrants from Africa wouldn’t qualify, nor would the descendants of slaves held in former French or British colonies. Would we need a new bureau to establish ancestry? Is that overhead and the work it will involve for black Americans to prove that they qualify worth it compared to creating a universal program that will most help the marginalized anyway? Or consider this dilemma: money for reparations will come from government expenditure, of which around half is funded by income tax. Could we be in a situation where we’re asking, say, a black Jamaican descendant of slaves, or a poor Latino immigrant, to help fund a program that they can’t benefit from? Reparations wouldn’t be quite such a zero-sum game, but it would (be) hard to shake the perception. Is this really the basis that we can build a majoritarian coalition? We have a real alternative: solidaristic policies that, unlike reparations, are actually the mass demands of African Americans.”

Sunkara’s argument is unconvincing, reductive and largely bankrupt of relevant historical context but that’s hardly the point. Far more troubling is that Sunkara is not African American — his Wikipedia page indicates his parents are East Indian immigrants from Trinidad and that he was raised in the New York City suburbs of Westchester County — yet a quick Google search of the terms “Guardian UK,” “reparations,” “U.S.” and “slaves” reveals that he is the only American commissioned by the paper thus far to opine on the topic of reparations.

Sunkara’s exalted status as the Guardian’s spokesman for 42 million black Americans is no accident but part of a broader media strategy to frustrate —if not deny altogether— the growing demands of the country’s most subjugated population for a fairer rate of return on our labor, and a more equitable distribution of opportunities.

The hubris on display is simply stunning: Sunkara and his peers infantilize African Americans by presuming to know what’s best for us. To fully understand the inherent racism, imagine a media milieu in which African Americans are routinely invited to speak on behalf of Jews.

At issue is not some jejune notion of diversity or the oft-mocked identity politics but rather a question of how best to incubate working-class political movements in America. While it’s true that no two revolutions are identical, the sine qua non of liberal democracy is a black working class that is able to speak for itself. The correlation between black self-representation and proletarian revolution dates back to the Civil war when slaves, aided and abetted by white abolitionists, waged a massive resistance campaign that the famed sociologist W.E.B. DuBois famously dubbed a general strike, forcing Abraham Lincoln to sign the Emancipation Proclamation before African Americans effectively freed themselves by simply walking off the plantations, refusing to work, or sabotaging the South’s entire agricultural yield.

That momentum, DuBois and others theorize, set in motion modernizing reforms such as public schools that defined the postbellum Reconstruction era, and created a template for American pluralist movements that peaked in 1973 when poverty reached historic lows, black membership in labor unions reached all-time highs, and African American intellectuals were, if not ubiquitous, visible participants in civic debates.

The pairing of rising income levels and loudening black voices in the public sphere is not a coincidence but the culmination of a grassroots campaign begun at the apogee of the Great Depression. The 40-year epoch that began with the New Deal was characterized by the most robust expression of class solidarity and interracial collaboration in American history. In union halls and the news media, on college campuses and movie theaters and Broadway stages, blacks largely eschewed interlocutors to speak for ourselves and participate vigorously in American public life.

One of the main sparks for this conflagration was the 1931 arrest of nine black teenagers near Scottsboro, Alabama for allegedly raping two white women aboard a train. For American communists, the crisis represented an opportunity to gain a foothold in the African American community; three years earlier, the 6th Congress of the Communist International had proclaimed:

“It is essential for the Communist Party to make an energetic beginning now-at the present moment-with the organization of joint mass struggles of white and black workers against Negro oppression. This alone will enable us to get rid of the bourgeois white chauvinism which is polluting the ranks of the white workers in America, to overcome the distrust of the Negro masses caused by the inhuman barbarous Negro slave traffic still carried on by the American bourgeoisie-in as much as it is directed even against all white workers-and to win over to our side these millions of Negroes as active fellow-fighters in the struggle for the overthrow of bourgeois power throughout America”

Despite scant and conflicting evidence, the Scottsboro Boys were convicted in April of 1931, and all but one, 13-year old Roy Wright, sentenced to die in the electric chair.

Survey after survey had already informed party leaders that their didactic pamphlets and journals did not produce the desired impact, and they decided instead to mount an international campaign which put the families of the falsely accused men front-and-center. Of those sent abroad was a widow and domestic servant from Chattanooga, Ada Wright, the mother of Roy and his older brother Andy who had been sentenced to death. Wright, one activist wrote later, couldn’t discern an “elephant from a Communist” but accompanied by an ILD lawyer, she toured 16 countries in the spring of 1932, and in her own words compared the plight of the Scottsboro boys to “class war prisoners all over the world.”

In a 2001 paper by George Washington University English Professor James A. Miller, and historians Susan Dabney Pennybacker, and Eve Rosenhaft wrote:

“She spoke in London, Manchester, Dundee, Kirkaldy, Glasgow, and Bristol, along with ILD organizers. Prime Minister Eamon De Valera prohibited Wright from entering Ireland. She traveled instead to Scandinavia, where 10,000 people reportedly demonstrated in Copenhagen alone. Wright and Engdahl again crossed the Belgian border illegally to visit the coal district of Wallonia in late August 1932. She addressed audiences of women in Charleroi and in Gilly, the heart of the “moving and often murderous arena” of the Borinage. When she was arrested in Charleroi, a crowd of mothers with babes in arms accompanied her to the police station. She was again arrested in Kladno, Czechoslovakia, on suspicion of spreading Communist propaganda with the intent to interfere in local politics: “I answered that I don’t know anything about local conditions in Kladno, that I’m not trained enough to give a political speech and I don’t know enough about Communism yet to be a good Communist.”

Still, her star turn on the European stage was a game-changer, winning hearts and minds by reimagining blacks as political actors and not merely passive victims, alternately persuading whites such as John Howard Lawson, the dean of the Hollywood 10, to diligently portray blacks as equal to whites in their film scripts, and many blacks to view communists as better allies than the black bourgeoisie as exemplified by the NAACP. So forceful a speaker was Wright that Franklin D. Roosevelt asked for regular updates on her subsequent European tours and even considered intervening in the case; all nine were eventually exonerated. Wright credited “the Russians” with saving her sons until the day she died. More importantly, Wright’s agency reified a budding biracial coalition that went on to assemble the most prosperous working class in history —months after her 1932 tour concluded, labor leader Harry Bridges toured black churches in the Bay area to enlist blacks to join the segregated dockworkers’ union — and inspired the civil rights, black power, Latino rights, LGBT, antiwar and feminist movements.

Anyone familiar with postcolonial studies will, of course, recognize the silencing of black voices as Orientalism, as defined in the late Edward Said’s groundbreaking 1978 book of the same name. Said posited that the West has historically sought to qualify its imperialism by assigning men of science and letters the exercise of shifting the blame for colonialism, from the colonizer to the colonized. The Palestinian Said named this brand of racist pseudoscience for the unfortunate term coined by the West to describe the Arab world to its East and dated its practice as far back as France’s 1798 invasion of Egypt, when Napoleon encouraged artists, writers, and anthropologists to re-imagine the Nile’s inhabitants, or to Orientalize the Orient. Of the famed French novelist’s depiction of a 19th-century dancer, Said wrote:

“Flaubert’s encounter with an Egyptian courtesan produced a widely influential model of the Oriental woman; she never spoke of herself, she never represented her emotions, presence, or history. He spoke for and represented her. He was foreign, comparatively wealthy, male, and these were historical facts of domination that allowed him not only to possess (her) physically but to speak for her and tell his readers in what way she was “typically Oriental.”

With the American Empire at its nadir, an insincere liberal class is doubling down on its efforts to control the narrative by squeezing authentic black voices out of the picture, and effectively claiming authorship of all revolution. Sources as disparate as the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal and Malcolm X explain why: in his 1944 tome, An American Dilemma, Myrdal attributes racist attitudes in the U.S. to simple jealousy, and Malcolm often said that the white liberal, and white conservative wanted the same thing, which was their turn at the top of a racial hierarchy.

As evidence, consider Sunkara’s myopic critique of reparations. He envisions reparations as a means-tested welfare program, the burden of which would be borne by other working-class Americans. But reparations could be viewed as as a means to an end, specifically sovereignty for African Americans in an effort to break an endless cycle of proletarian revolt in which whites begin to collaborate with blacks to combat a catastrophic crisis, only to again repudiate their fellow black coworkers once the threat has subsided.

In that context, reparations could take the form of autonomous empowerment zones financed by tax receipts gleaned from downtown business districts or a surtax on the very banks which targeted blacks and Latinos with fraudulent subprime home loans. You needn’t be a Marxist to understand that such an approach could, in fact, unite black and white workers rather than polarize us.

Whatever the fix, the Guardian’s readers would almost certainly have been far better informed on the issue if it had been written by any number of African American intellectuals who retain working-class credentials such as Anthony Monteiro, Sandy Darity, or Frank Wilderson, activist/writers such as Mel Reeves, Thandisizwe Chimurenga, and Kevin Alexander Gray, or journalists such as Sunni Khalid, Nolu Crockett Ntonga, Kenneth Walker, Margaret Kimberly, Glenn Ford, Thandisizwe Chimurenga, LeRon Barton or Esther Iverem.

Taken in its totality, the silencing of black radical voices works in tandem with the news media’s abandonment of storytelling to isolate the very people who have historically been engines of modernization. Amplifying black voices is not intended as some kind of precious paean to identity politics but as a tactic for grinding out a win in America’s class war by centering the nation’s most ferocious class warriors.

In her iconic 1983 essay, Can the Subaltern Speak?, the Indian scholar Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak explores the power dynamics inherent in silencing the most marginalized populations.

If the American working class is to ever be free, we better all pray the answer to Spivak’s question is “yes!”

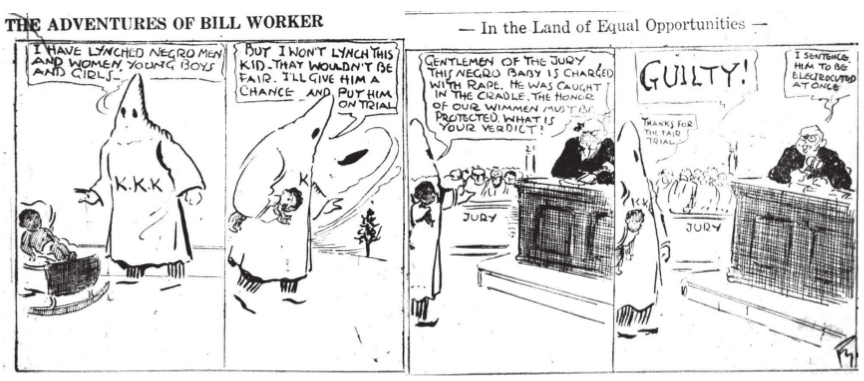

1931 cartoon in the communist periodical, the Daily Worker