Two to Tango: Michael Jordan’s Sad Legacy as the Plutocrats’ Champ, and the Anti-Ali

Five years ago on a bitterly cold day in February, I walked into a Bohemian coffee bar on Chicago’s Westside to interview Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn, the husband-and-wife couple who helped found the Leftist organization of young white militants known as the Weather Underground. For the two- and- a half hours that followed, I sat in rapt astonishment while these two regaled me with stories of their days on-the-run, of the Black Panthers and Emmet Till and their thoughts on everything from Ferguson to Occupy and immigrants’ rights. About halfway through, Bernardine recalled how she got her start in the movement as a young law student helping to organize rent strikes in black neighborhoods on Chicago’s Southside.

Of the dozens of boycotts she helped arrange, only one, she recalled proudly, resulted in an eviction, and on the morning Cook County sheriff’s deputies executed the order, throngs of restive black volunteers gathered outside the apartment to load the family’s furniture onto a moving van. Bernardine was at the front of the crowd, and when the doors to the apartment opened, the neighbors began to heave and surge like a volcano preparing to vomit. Dohrn could sense one of the black men towering behind her and as he rushed past he handed her his sports coat for safekeeping. Handling the jacket, Dohrn couldn’t help but notice that the material was fine and expensive, and not usually what you’d expect to see worn by a member of Chicago’s black working class. It was only when he came to retrieve the jacket that she recognized its owner as one Muhammad Ali.

Thirty years later, a throng of reporters assembled around the locker of another resplendent Chicago athlete by the name of Michael Jeffrey Jordan to ask his thoughts about Nike’s exploitation of child workers in southeast Asian sweatshops “I think that’s Nike’s decision to do what they can to make sure everything is correctly done,” he said. “I don’t know the complete situation. Why should I? I’m trying to do my job. Hopefully, Nike will do the right thing, whatever that might be.”

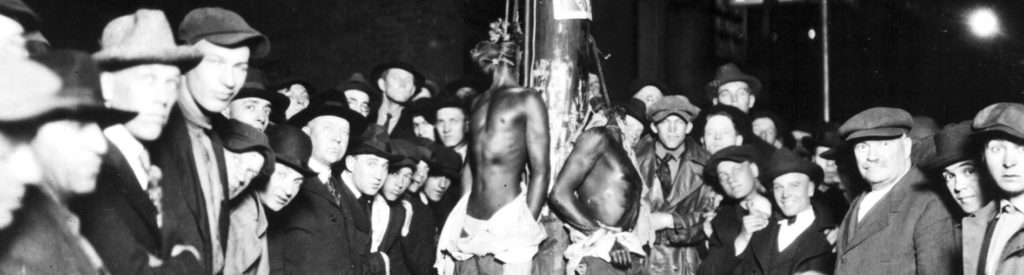

Two transcendent black athletes, two polar opposite responses to suffering, with Ali– the People’s Champ– hurtling into the breach to come to the aid of his community and Jordan doing all he could to distance himself from an exploited class of darker-skinned people who were literally manufacturing much of his wealth.

Netflix last week debuted a 10-part documentary, the Last Dance, that examines in sharp relief Jordan’s final championship season with the Chicago Bulls. Less than halfway through the mini-series, quarantined sports pundits are mostly engorged with praise for Jordan’s athleticism and myopic commitment to winning at all costs. And to be sure, Jordan, the basketball player, was a revelation. When he was on the court you simply couldn’t take your eyes off of him. I remember as a young man trying to chat up women at bars and becoming so engrossed in watching Jordan on the television screen that I simply lost interest in my date.