Five years ago on a bitterly cold day in February, I walked into a Bohemian coffee bar on Chicago’s Westside to interview Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn, the husband-and-wife couple who helped found the Leftist organization of young white militants known as the Weather Underground. For the two- and- a half hours that followed, I sat in rapt astonishment while these two regaled me with stories of their days on-the-run, of the Black Panthers and Emmet Till and their thoughts on everything from Ferguson to Occupy and immigrants’ rights. About halfway through, Bernardine recalled how she got her start in the movement as a young law student helping to organize rent strikes in black neighborhoods on Chicago’s Southside.

Of the dozens of boycotts she helped arrange, only one, she recalled proudly, resulted in an eviction, and on the morning Cook County sheriff’s deputies executed the order, throngs of restive black volunteers gathered outside the apartment to load the family’s furniture onto a moving van. Bernardine was at the front of the crowd, and when the doors to the apartment opened, the neighbors began to heave and surge like a volcano preparing to vomit. Dohrn could sense one of the black men towering behind her and as he rushed past he handed her his sports coat for safekeeping. Handling the jacket, Dohrn couldn’t help but notice that the material was fine and expensive, and not usually what you’d expect to see worn by a member of Chicago’s black working class. It was only when he came to retrieve the jacket that she recognized its owner as one Muhammad Ali.

Thirty years later, a throng of reporters assembled around the locker of another resplendent Chicago athlete by the name of Michael Jeffrey Jordan to ask his thoughts about Nike’s exploitation of child workers in southeast Asian sweatshops “I think that’s Nike’s decision to do what they can to make sure everything is correctly done,” he said. “I don’t know the complete situation. Why should I? I’m trying to do my job. Hopefully, Nike will do the right thing, whatever that might be.”

Two transcendent black athletes, two polar opposite responses to suffering, with Ali– the People’s Champ– hurtling into the breach to come to the aid of his community and Jordan doing all he could to distance himself from an exploited class of darker-skinned people who were literally manufacturing much of his wealth.

Netflix last week debuted a 10-part documentary, the Last Dance, that examines in sharp relief Jordan’s final championship season with the Chicago Bulls. Less than halfway through the mini-series, quarantined sports pundits are mostly engorged with praise for Jordan’s athleticism and myopic commitment to winning at all costs. And to be sure, Jordan, the basketball player, was a revelation. When he was on the court you simply couldn’t take your eyes off of him. I remember as a young man trying to chat up women at bars and becoming so engrossed in watching Jordan on the television screen that I simply lost interest in my date.

But there is also this: as a man, Jordan was an abject failure, who as a rule turned his back on his tribe, his community and the working class into which he was born, and, from all evidence, passed up every opportunity to ease the suffering of other human beings. He famously refused his mother’s entreaties to support the black, liberal Democrat, Harvey Gantt, in a closely contested 1990 U.S. Senate race against North Carolina’s cartoonish segregationist, Jesse Helms, reportedly responding that “Republicans buy shoes too” referencing his lucrative endorsement deal with Nike. He declined to attend or support the 1995 Million Man March because, he told former New York Times columnist, William Rhoden, “I take care of my kids.” Charles Barkley once told Oprah Winfrey that Jordan is the cheapest man he knew, routinely telling panhandlers to go get a job at Mcdonalds, and the rapper, Chamillionaire, says Jordan humiliated him for asking for a photograph with the then-retired baller.

But the piece de resistance occurred before the 1991 NBA finals between the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers when Bulls’ guard Craig Hodges approached Jordan and Lakers superstar Magic Johnson about boycotting the opening game to protest state terror against blacks as exemplified by the Los Angeles Police Department’s videotaped beating of an unarmed motorist, Rodney King, three months earlier. As Hodges recalled the incident for reporters years later, he proposed standing “ in solidarity with the black community while calling out racism and economic inequality in the NBA, where there were no black owners and almost no black coaches despite the fact that 75 percent of the players in the league were African American.”

Jordan gaslit Hodges as “crazy.”

The financial calamities confronting the U.S. today did not begin with the onset of a global pandemic three months ago but a social scourge that first began to infect the American body politic following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. who before his death prophesied that racial integration would subsume African Americans “into a burning house.” Along with Oprah and Obama and Kamala Harris and Cory Booker and thousands of other black professionals who are, in effect, defectors, Jordan embodies the immolation of an African-American dialectic that married commerce and community, modernized the state, and exalted the individual only inasmuch as he or she helped to lift up the people who produced them.

With athletes and politicians like Ali, and King and Curt Flood and Paul Robeson and Tommie Smith and John Carlos helping shoulder some of the load, the American working class, generally, and blacks, specifically, were demanding a fairer return on their labor. By 1973, wages, household savings, and the number of workers belonging to labor unions were at an all-time high, while fewer Americans lived in poverty than ever before or since. In 1973, there were 317 work stoppages involving at least 1,000 employees, and 424 the following year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Today, even before anyone heard of the coronavirus, wages, savings and the percentage of unionized employees had plummeted to historic lows, the national poverty rate has soared to historic highs, and there were seven work stoppages in 2017, the last year for which figures are available.

Seven.

This was not an accident. With the workers raising their flag in one battle after another beginning in the depths of the Great Depression, the wealthiest one percent and their vassals in government began to regroup in the early 1970s, and gather momentum with Ronald Reagan’s election. Critical to this bipartisan counterrevolution was using the news and entertainment media, the academy, nonprofits and political parties to marginalize and silence the African American voices that were often loudest in articulating proletarian demands on capital. Jordan was merely a cog in that effort to depoliticize athletes, and effectively weaponize sports as an entertaining distraction from the class struggle, similar to plantation owners pitting slaves against each other in the boxing ring, or fielding baseball teams to allow exploited Central American farmworkers to let off steam.

“Our generation dropped the ball as a lot of us were more concerned with our own economic gain,” Hodges said. “We were at that point where branding was just beginning and we got caught up in individual branding rather than a unified movement.”

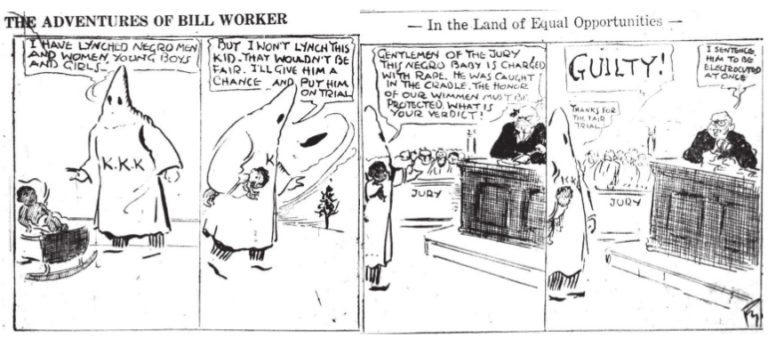

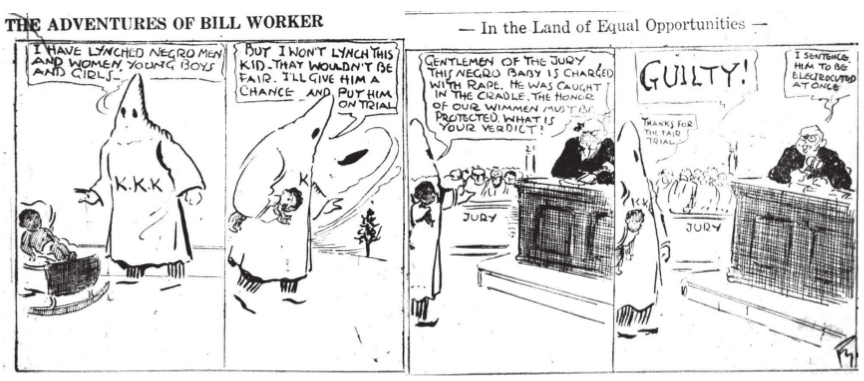

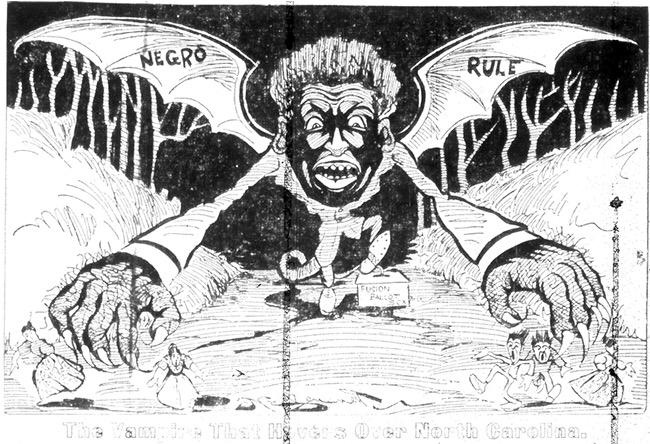

LeBron James and Colin Kaepernick and Carmelo Anthony and Eric Reid and the Bennett brothers and a generation of professional athletes who came of age in the 1990s when Cliff Huxtable was no longer on the air, Jordan was winning championships, and jobs in the American inner-city were disappearing, are more likely to speak out on behalf of the black community. Seemingly conscious of his shameful legacy, Jordan has belatedly begun to speak out against police violence, and contribute to charitable causes although he continues to underwhelm with his political and racial consciousness. Growing up in Wilmington, North Carolina where a cabal of white supremacists in 1898 organized a pogrom which murdered as many as 300 African Americans, Jordan told a book author in 2014 that he threw a soda at a white high school classmate who called him the N-word. The moral of Jordan’s story? He was guilty of reverse racism.

More recently, Jordan has defended his apolitical stance during his playing career as part of his commitment to winning, which, ironically enough, harkens back to arguments used to defend savage racist coaches like Adolph Rupp, Bear Bryant and Bobby Knight. Jordan’s reputation among poor and working-class African Americans is strikingly similar to Pele’s with impoverished black Brazilians, who resent the soccer legend’s cozy relationship with the military junta that ruled Brazil for a generation.

“When I was playing, my vision – my tunnel vision – was my craft,” Jordan said recently. “Now I have more time to understand things around me.”

But that just doesn’t fly if you are profiting from the exploitation of Vietnamese girls as young as 12. And the Last Dance depicts Jordan as even indifferent to the contract struggle of his Bulls’ teammate, Scottie Pippen. As we stare down a pandemic that threatens to finish off the American working class, perhaps we should refrain from debates of whether Jordan is the GOAT, or greatest of all-time, and instead keep in mind the words of another Chicagoan who, as legend has it, dreamt of playing center field for the New York Mets, but gave his life to the people instead.

Here’s Fred Hampton:

“If you walk through life and don’t help anybody, you haven’t had much of a life”